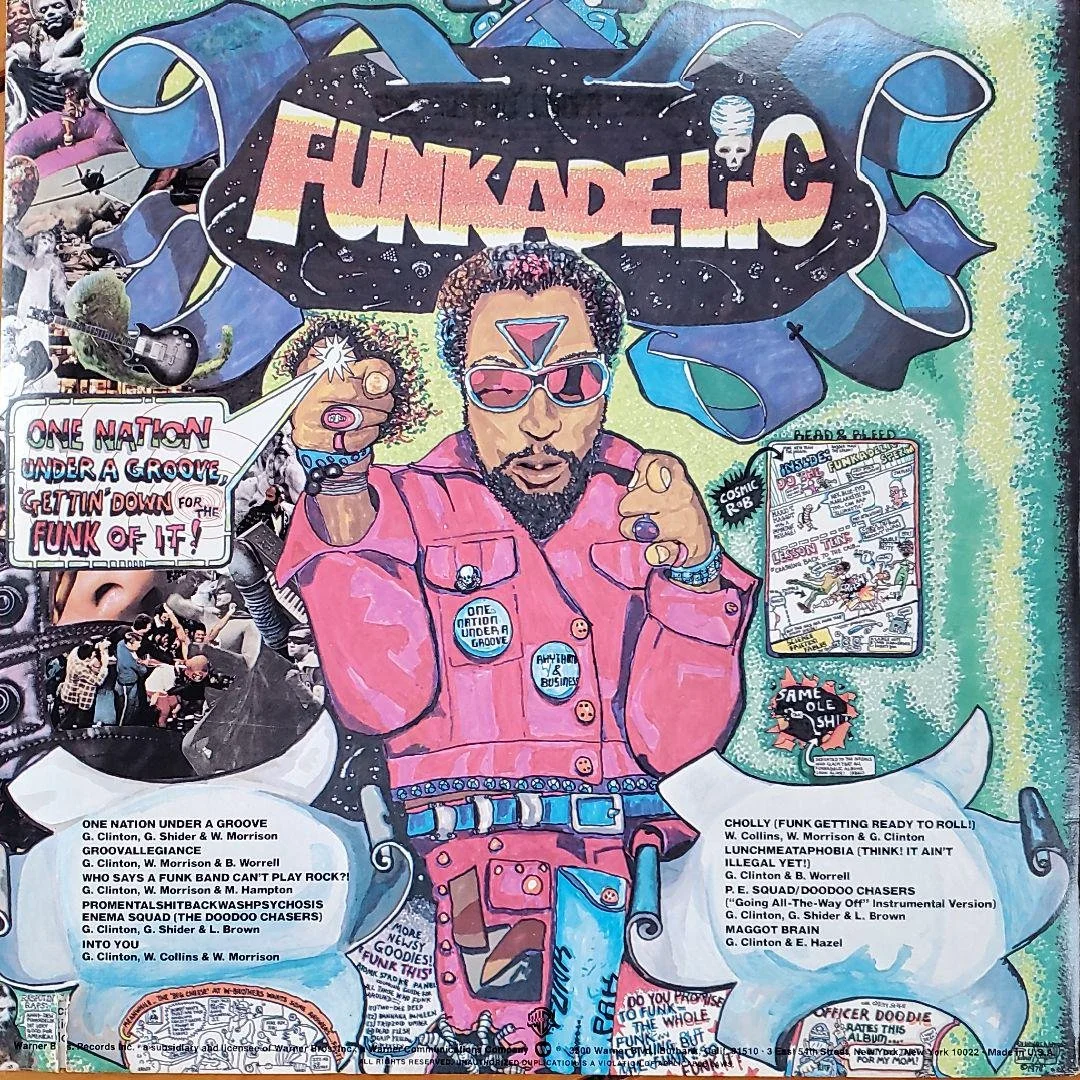

P-Funk Propagandist Pedro Bell

Artist self-portrait

The first time I had heard of either Noam Chomsky or the Trilateral Commission was within the liner notes and art of the Funkadelic hit album ‘One Nation Under a Groove’. Many of the funk band’s album cover art contained subversive content hidden within their psychedelic magic marker-rendered masterpieces. The band itself, founded and led by George Clinton, recorded subversive music with lyrics that disguised their political leanings, much of it informed by the work of Chicago artist Pedro Bell. It was his artwork that pushed the “-delic” (psychedelic) of Funkadelic to another plane of WTF-ism.

Gatefold album cover for Let’s Take it to the Stage

Pedro was my friend and big brother (as he was, I would one day learn, to many young aspiring artists). We would talk for hours while I listened to his stories about his (mis)adventures during his time with the P-Funk family. One day I received a package in the mail from him and when I opened it and removed the items from within, it felt as though I had opened a time capsule. There enclosed were buttons, posters, comics, stickers, newsletters, and more from the seventies. The feeling of holding something in my hand from a time I often romanticized but never experienced was immediately electric! We were friends for several years, but I lost track of him sometime in 2008. He had become color-blind in 1996 and eventually blind altogether. In his last correspondence to me, the only thing I can recall him saying is “I’m only rich in theory” (though I don’t remember what his comment was in reference to, nor the conversation itself). Sadly, Pedro Bell died in poverty on August 27, 2019.

Inner album cover, essay, and liner notes for Let’s Take it to the Stage

Shortly after Pedro’s death, a statement released by P-Funk bassist, Bootsy Collins, spoke about Pedro’s influence on P-Funk music and culture.

“The wild and bizarre artwork gave our early audience a sense of seeing the visual side of the music and the language. He had a way of translating and communicating what all the weirdness was about, and that you, the consumer, really wanted to figure it out, because it truly was otherworldly. Every time the two were done together, it would create The One. They there would be another satisfied customer! Thanks to our Captain Draw, the Clone Stranger of Artistic Gratification to the Nation, Mr. Pedro Bell. The Funk got Stronger. Your service to this world can never be calculated.”

Funkadelic band members from Let’s Take it to the Stage

But for his failing health, Pedro would have been able to pursue opportunities that would have earned him more than the pittance he received for album covers. He not only inspired artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, his artwork laid the foundation for Afro-futurism. One look at the pages in DeviantArt will tell you that Pedro’s art would have fit right in amongst many of today’s young subversive artists, and I’d like to think that some of those young artists were perhaps influenced by Pedro’s art. The executives at Warner Brothers Records, however, knew how invaluable his art was because, as Pedro once claimed, they stole some of it (they were hostile toward the whole P-Funk organization, according to rumors). Pedro designed the Funkadelic logo, and for more than a decade (from 1981), Warner prevented George Clinton from using the “Funkadelic” name., Many years later when they returned the band name to Clinton, he was prevented from using the skull in The Funkadelic logo that served as the dot over the “i” (petty as fuck, but the “i” has since been returned). Apparently, they didn’t hold onto it for long, since almost all of Pedro’s art somehow ended up in museums in countries outside the U.S.

Inside gatefold cover

When Pedro Bell died, I had the intention of composing something of a memorial to pay my respects, but I stared at an empty page for months, until the COVID -19 pandemic hit, and I eventually forgot until now. The reason for my timing is that I think Pedro would love Neuerotica. He would have dug my luxury e-magazine, but he would like to think he would have been impressed with what I’m doing now. He would notice his influence in the kinds of content I publish within the virtual pages of Neuerotica. Our fusion of subversive art, music, fashion, culture, and politics is a concept I borrowed from his writing and art. If he were still alive, this would have been an interview rather than an article.

Gatefold album cover for Hardcore Jollies

It can not be overstated that Pedro Bell is one of the most overlooked artists in African American history. In an interview with the New York Times, Rebecca Alban Hoffberger, founder of the American Visionary Art Museum, calls Bell “a real unsung hero”. Historians of African American history and art should hasten to include Pedro’s art and legacy into their classrooms and publications. Pedro’s work has earned the honor of being worthy of examination and study. His scathing commentary on race, politics, corrupt business practices within the music industry, and more concealed in both his wordplay and art is, to this day, unparalleled.

Below is an essay (edited solely for grammar) published on the George Clinton website. Unfortunately, no attribution can be found anywhere on said website, and the contact link only links to their newsletter subscription form. I have republished it here with a link to the original article, and there are links to where the article originated, as well as other sources of information about Pedro Bell.

Pedro Bell in art gallery, photo by Jean Lachat/Chicago Sun-Times

Funkadelic had been alarming/converting audiences for around four years before he showed up. Hindsight shows that in those years, between 1969 and 1973, they were trying anything and everything like they had nothing left to lose. Which they didn’t since they were on an obscure label, an erratic circuit, and haphazardly building an odd cult of fans while being run out of towns.

Pedro was, like many of those fans, a young person into the hothouse explosion of hybrid musics that gushed over from the expansive late 60s. Like the deepheads, he loved Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, Sun Ra, Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, The Beatles. He particularly liked the distinct and disturbing packaging of Frank Zappa albums. It gave a special identity to the artist and to the fans who dug it. It plugged you into your own special shared universe. So he sent elaborately drawn letters to Funkadelic’s label with other samples. George Clinton liked the streetwise mutant style and asked him to do the “Cosmic Slop” album cover in 1973.

Gatefold album cover for Cosmic Slop

That was the moment Funkadelic became everything we think about them being.

Before, Funkadelic used shocking photos of afro-sirens along with liner notes lifted from the cult, Process Church Of The Final Judgment. Very sexy, very edgy. But looking a bit too much like labelmates The Ohio Players’ kinky covers, and reading like a Charles Manson prescription for apocalypse. A more cartoonish cover for the fourth album “America Eats Its Young” (1972) along with more coherent production and song structure was a new start. But Pedro crystallized their identity to the world with that next LP.

In 1973, there was no MTV, no internet, no VCRs, no marketing strobe in all media. An act toured, they put out an album once a year, and they were lucky to get a TV appearance lip-synching a hit. You couldn’t tape it, and you were lucky to even see them. As a fan, almost your whole involvement with the band came through the album cover. It was big, it opened out in a gate fold, there were inserts and photos and posters. Sitting with your big ol’ headphones, you shut off the world and stared at every detail of the album art like they were paths to the other side, to the Escape. Who were all those people in the “Sgt. Pepper” crowd?; what alternate reality were artists Roger Dean (Yes) and Mati Klarwein (Santana, Miles Davis) from?; why are the burning businessmen shaking hands?; is it an African woman standing or a lion’s face?; does it say “American Reality” or “American Beauty” or both?

This was an art era for an art audience. Posters, T-shirts, LPs. These were your subculture badge of honor, your spiritual battle cry, your middle finger to mediocrity. They took every cent you had saved and were even harder to come by, which made it even more personal, more rebel. Your LP was a shield, your T-shirt was armor. They got you expelled, ostracized, beat up. They scared the living hell out of the straights around you…and you loved that. It reaffirmed your faith that you were into something good, something unique.

George Clinton’s Computer Games album cover

What Pedro Bell had done was invert psychedelia through the ghetto. Like an urban Hieronymus Bosch, he cross-sected the sublime and the hideous to jarring effect. Insect pimps, distorted minxes, alien gladiators, sexual perversions. It was a thrill, it was disturbing. Like a florid virus, his markered mutations spilled around the inside and outside covers in sordid details that had to be breaking at least seven state laws.

More crucially, his stream-of-contagion text rewrote the whole game. He single-handedly defined the P-Funk collective as sci-fi superheroes fighting the ills of the heart, society, and the cosmos. Funk wasn’t just a music, it was a philosophy, a way of seeing and being, a way for the tired spirit to hold faith and dance yourself into another day. As much as Clinton’s lyrics, Pedro Bell’s crazoid words created the mythos of the band and bonded the audience together.

Funkcronomicon album cover

Half the experience of Funkadelic was the actual music vibrating out of those wax grooves. The other half was reading the covers with a magnifying glass while you listened. There was always more to scrutinize, analyze, and strain your eyes. Funkadelic covers were a hedonistic landscape where sex coursed like energy, politics underlay every pun, and madness was just a bigger overview.

Pedro called his work ‘scartoons’, because they were fun, but they left a mark. He was facing the hard life in Chicago full-on every day with all the craft and humor he could muster.

Pedro’s unschooled, undisciplined street art gave all the Suit execs fits, as when the cover for “Electric Spanking of War Babies” caused such a scandal that it had to be censored before release. It also opened the door for all the great NYC graffiti artists of the late 70’s, for the mainstream success of Keith Haring’s bold line cartoons, and James Rizzi’s marker covers and “Genius of Love” video animation for The Tom Tom Club.

Album cover for United State of Mind by Enemy Squad

When Parliament and Funkadelic went on hiatus in the 80s, it was Pedro Bell’s art that gave the P-Funk identity to George Clinton’s albums like “Computer Games” (1982), “You Shouldn’t-nuf Bit Fish” (1983), “Some of My Best Jokes Are Friends” (1985), and “R&B Skeletons In the Closet” (1986); as well as spin-offs like Jimmy G & The Tackhead’s “Federation of the Tackheads” (1985), and his clay figure art for INCorporated Thang Band’s “Lifestyles of the Roach and Famous” (1988).

By the early 90’s the game had changed and not to Pedro’s favor. MTV had turned every song into a jingle, and every album into a quarterly marketing plan. Every star’s face was in your face every place all over the place, milking an album for three years until the next committee go-round. CDs shrunk the album cover experience into a coaster. The days of swimming in your LP cover were gone. (But conversely, Rock concert poster design exploded, as fans were desperate to have some great art to fill the void.)

Flyer for house/dance group Deee-Lite

During the decade Pedro continued soldiering on with the CD covers for P-Funk-inspired bands like Maggotron’s “Bassman of the Acropolis” (1992), “Funkronomicon” for Bill Laswell’s all-star funk collective, Axiom Funk (1995), and Enemy Squad’s “United State of Mind” (1998). And of course for George Clinton’s “Dope Dogs” (1994),”TAPOAFOM (The Awesome Power of a Fully Operational Mothership)” (1995) and “Greatest Funkin’ Hits” (1996); and P-Funk’s “How Late Do You Have 2 B B4 U R Absent?” (2005).

In the meantime his style was homaged/appropriated/bit by other artists designing for Digital Underground, Miami Bass groups, and dodgy Funkadelic compilations. But he received better due with a great write-up in the countercultural art magazine Juxtapoz (#16, Fall ’98). He also had a couple of his Funkadelic covers in Rolling Stones’ “Greatest album covers of all time” issue.

Below are links to more articles about Pedro Bell, as well as a link to the P-Funk website.

George Clinton, Lambiek Comiclopedia, Rolling Stone, New York Times